-

What Border Crisis? Mexican Migrant Shelters Are Quiet Ahead of Trump - 3 hours ago

-

Southern California in ‘uncharted territory’ as fire weather returns all next week - 3 hours ago

-

New Trump Meme Comes With a Legal Waiver - 4 hours ago

-

Mexican Mafia leader offered protection to El Chapo, prosecutors say - 10 hours ago

-

H-E-B Food Recalls: Full List of Products Impacted - 10 hours ago

-

Explosions Heard in Ukraine’s Capital - 13 hours ago

-

TikTok Says App May Be ‘Forced to Go Dark’ In New Update - 15 hours ago

-

‘This has been really devastating’: Inside the lives of incarcerated firefighters battling the L.A. wildfires - 16 hours ago

-

Joe Biden’s Average Approval Compared to Donald Trump Compared: Poll - 21 hours ago

-

Commentary: Ashes still drifting through L.A. are a valuable reminder - 23 hours ago

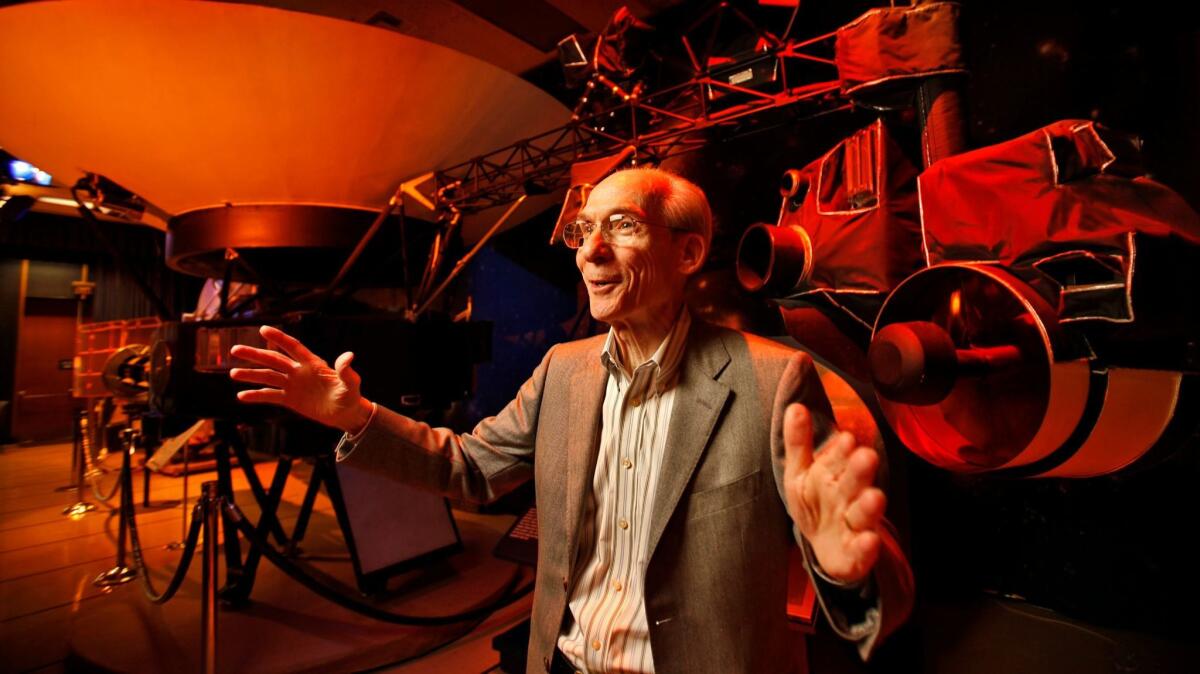

Ed Stone, JPL director and top Voyager scientist, dies at 88

Ed Stone, the scientist who guided NASA’s breakthrough Voyager mission to the outer planets for 50 years and led the Jet Propulsion Laboratory when it landed its first rover on Mars, died Tuesday. He was 88.

A physicist who got in on the ground floor of space exploration, Stone played a leading role in NASA missions to Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. The discoveries made under his watch revolutionized scientists’ understanding of the solar system and fueled humanity’s ambition to explore distant worlds.

Carolyn Porco, who worked on imaging on JPL’s Voyager and Cassini missions, called Stone “a thoroughly lovely man” who was “as close to perfect as a project scientist could ever be.”

“When two science teams were in contention over some spacecraft resource, and Ed had to decide between the two, even the guy who lost went away thinking, ‘Well, if this is what Ed has decided, then it must be the right answer,’” Porco said by email Tuesday. “I feel blessed to have known Ed. And like many people today, I’m very sad to know he’s gone.”

Stone was a 36-year-old Caltech physics professor in 1972 when he was asked to serve as chief scientist for an audacious plan to send a pair of spacecraft to explore the solar system’s four giant planets for the first time.

It was the opportunity of a lifetime, but he wasn’t sure he wanted the gig.

“I hesitated because I was a fairly young professor at that point. I still had a lot of research I wanted to do,” he recalled 40 year later.

He took it anyway, and from the mission’s first encounter with Jupiter in 1979 to its final flyby of Neptune in 1989, Stone became the scientific face of the Voyager mission. He guided the science agenda and helped the public make sense of revolutionary images and data not just from Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, but from many of their fascinating moons.

Stone and his more than 200 science collaborators were the first to discover lightning on Jupiter and volcanoes on its moon Io. They spotted six never-before-seen moons around Saturn and found evidence of the largest ocean in the solar system on Jupiter’s moon Europa, as well as geysers on Neptune’s moon Triton.

“It seemed like everywhere we looked, as we encountered those planets and their moons, we were surprised,” Stone told the Los Angeles Times in 2011. “We were finding things we never imagined, gaining a clearer understanding of the environment Earth was part of. I can close my eyes and still remember every part of it.”

The Voyager 1 spacecraft became the first manmade object to reach interstellar space in 2012, and Voyager 2 followed suit in 2018.

Stone, pictured with a model of the Voyager spacecraft, said the discovery of volcanoes on Io was a highlight of the mission.

(NASA)

The twin probes continue to send weekly communications to Earth from interstellar space. Stone retired in 2022 on the mission’s 50th anniversary.

“A part of Ed lives on in the two Voyager spacecraft. The fingerprints of his dedication and keen leadership are woven into the Voyager mission,” said Linda Spilker, who joined the mission in 1977 and succeeded him as project scientist.

The Voyager mission was Stone’s crowning achievement, but hardly his only one.

He was a principal investigator on nine NASA missions and a co-investigator on five others, including several satellites designed to study cosmic rays, the solar wind and the Earth’s magnetic field.

He became director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge in 1991, a role he held for a decade.

It was an era of cost-cutting at NASA, but Stone still managed to launch Galileo’s five-year mission to Jupiter and send the Cassini spacecraft to Saturn. He was also at the agency’s helm when Mars Pathfinder delivered the Sojourner rover to the Red Planet. It marked the first time that humans had put a robotic rover on the surface of another planet.

Throughout his tenure at JPL, Stone continued to work and teach at Caltech, even teaching freshman physics during some of Voyager’s long cruise times between planets.

He also served as chairman of the board of the California Assn. for Research in Astronomy, which is responsible for building and operating the W.M. Keck Observatory and its two 10-meter telescopes on Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

Edward Carroll Stone Jr. was born in Iowa on Jan. 23, 1936, and grew up in Burlington, where his father ran a small construction business and his mother kept the company books.

The eldest of two brothers, Stone was attracted to science from a young age. Under his father’s watchful eye, he learned how to take apart and reassemble all varieties of technology, from radios to cars.

“I was always interested in learning about why something is this way and not that way,” Stone told an interviewer in 2018. “I wanted to understand and measure and observe.”

After studying physics at Burlington Junior College, he received his master’s and doctorate at the University of Chicago. Shortly after he began his graduate studies, news broke in 1957 that the former Soviet Union had launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite.

“Just like that, because of the Cold War and our need to match Sputnik, a whole new realm absolutely opened up,” he said.

Stone built a device for measuring the intensity of solar energetic particles above the atmosphere that hitched a ride to space aboard an Air Force satellite in 1961. Unfortunately the spacecraft’s transmitter didn’t work, so only a very limited quantity of data was returned to Earth. However, it was still enough to indicate that the intensity of the particles was lower than expected.

Despite the transmitter glitch, Stone said the project was thrilling. “We were taking the first steps in a whole new area of research and exploration,” he said. “We were right at the beginning.”

He joined the faculty at Caltech in 1964 and created more space experiments, this time for NASA.

Stone’s particular area of interest was cosmic rays — high-speed atomic nuclei that can originate from explosive events on the sun or from violent events beyond the solar system.

One of his cosmic-ray experiments was included among the 11 major Voyager experiments.

Ed Stone in 2011, about a year before Voyager 1 entered interstellar space.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Colleagues praised Stone for his leadership of the Voyager science team.

“He was a great hero, a giant among men,” said Porco, adding that Stone was known to treat everyone — from top scientists to graduate students — with respect.

Voyager team scientist Thomas Donahue put it this way: “Over the years, Ed Stone has proved to be remarkably adept at keeping a bunch of prima donnas on track.”

Stone was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1984 and received the National Medal of Science from President George H.W. Bush in 1991 in recognition of his leadership of the Voyager mission. He won the Shaw Prize in Astronomy in 2019, an honor that comes with a $1.2-million award. In 2012 his hometown of Burlington, Iowa, named its new middle school after him.

“This is truly an honor because it comes from the community where my exploration journey began,” Stone told a local newspaper.

Decades after Voyager’s launch he was asked to select his favorite moment from the mission. He chose the discovery of volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io.

“Finding a moon that’s 100 times more active volcanically than the entire Earth, it’s really quite striking,” he said. “And this was typical of what Voyager was going to do on the rest of its journey through the outer solar system.

“Time after time, we found that nature was much more inventive than our models,” he said.

His wife, Alice, whom he met on a blind date at the University of Chicago and married in 1962, died in December. The couple are survived by their two daughters, Susan and Janet Stone, and two grandsons.

Source link