-

Could Lake Mead End Up Drying Out Like the Ill-fated Aral Sea? - December 26, 2023

-

A portion of Mulholland Drive, damaged by mudslides in winter storms, reopens - May 26, 2024

-

‘Maybe You Don’t Want to Win’ - May 26, 2024

-

Donald Trump Putting Law Enforcement in Danger: Attorney - May 25, 2024

-

Avoid the waters of these 5 L.A. County beaches this holiday weekend, public health officials say - May 25, 2024

-

Bawdy Comedy ‘Anora’ Wins Palme d’Or at Cannes Film Festival - May 25, 2024

-

Map Shows Heat Wave Zone Spread Into Five New States - May 25, 2024

-

Azusa police arrest suspected slingshot-wielding vandal - May 25, 2024

-

Donald Trump Hammers Judge Ahead of Jury Instructions - May 25, 2024

-

Sometimes U.S. and U.K. Politics Seem in Lock Step. Not This Year. - May 25, 2024

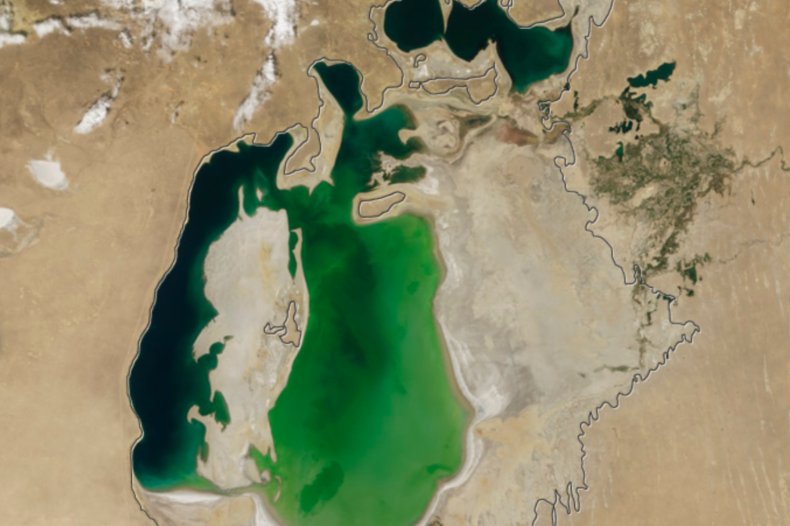

Could Lake Mead End Up Drying Out Like the Ill-fated Aral Sea?

The Aral Sea used to be the fourth-largest lake in the world, but thanks to poor water management, the lake rapidly shrank over only a handful of decades—from larger than the entire state of West Virginia to only 10 percent of its original size.

Now, some are concerned that the same fate may meet important reservoirs in the United States like Lake Mead.

Scorched by the megadrought that has gripped the U.S. southwest for 20 years, Lake Mead is constantly plagued by bouts of drying. The reservoir, which provides essential water to millions of people, is at risk of drying out further with the effects of climate change and water use modification.

Drag slider

to compare photos

The Aral Sea used to encompass around 26,300 square miles between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The lake started to shrink due to water being rerouted to supply irrigation projects for the Soviet Union in the mid-20th century. Rivers that usually fed the lake were instead redirected to the nearby desert in the hopes of growing more cotton, melon, rice and cereal crops.

However, many of these irrigation canals were poorly built and, as a result, not waterproof, allowing huge volumes of water to escape from the system and evaporate.

“The Aral Sea in Central Asia used to be the fourth largest lake in the world. In what has been described as the world’s worst environmental disaster since the 1960s, it has shrunk by over two-thirds because of industrial-scale water abstractions. Upstream water in Uzbekistan having been used to irrigate fields of ‘white gold’—thirsty cotton,” Timothy Clack, an associate professor and director of the Climate Change & (In)Security Project at the University of Oxford, told Newsweek.

In the 1960s, the lake level was dropping by around 8 inches every year, tripling to about 20 to 24 inches every year by the 1970s, and even 31 to 35 inches annually in the 1980s. By 1998, the lake had seen its area drop by 60 percent, down to only 11,000 square miles: around the same size as Hawaii. In the 25 years since, it has only shrank further.

This disappearance of the water led to major issues in the communities originally bordering the shrunken lake.

“Unsurprisingly, the fishing and processing industries—the bastion of the Soviet economy in the area—were decimated leading to loss of livelihoods and mass outmigration. There have been significant health implications for those that have remained,” Clack said. “Chemicals from fertilizers, pesticides and gas extraction, for example, have polluted the air and drinking water. Carcinogens in the air have caused throat and lung cancers and other respiratory diseases. Women locally are advised not to breastfeed their babies.”

“Similar indications of water scarcity are found elsewhere. Water security is one of the greatest and most underreported threats faced across the world today. There is no life without water,” he said.

Lake Mead, situated on the Colorado River between Arizona and Nevada, has seen record-low water levels due to the drought conditions in the area, pushing the reservoir closer and closer to dead pool level, at which point the water will no longer flow out through the Hoover Dam. The lake provides water and hydroelectric power to over 25 million people in the surrounding states, but increased water demand is putting further pressure on the reservoir and the Colorado River.

Image obtained from the University of Maryland Global Land Cover Facility / Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer MODIS on NASA’s Terra satellite

“We have certainly seen declines in lake water level in Lake Mead in the last few decades in response to the long drought in the region. Last year was an exception, but it’s not enough to fully refill the lake,” Tamlin M. Pavelsky, an associate professor of global hydrology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told Newsweek.

“So it’s similar to the Aral Sea in that human water withdrawals and climate change are affecting its water levels substantially. However, it’s also different in the sense that we can control how much water flows out of it and down the Colorado,” he said.

“Lake Mead is different—it’s a reservoir, and there is a river flowing in and flowing out. This makes the lake different from a closed lake in important ways, including that it’s not salty,” he said. “If you want a more perfect analog for the Aral Sea in the United States, I would look at the Great Salt Lake, where we have major declines in water level that are substantially affecting the area of the lake and the ecosystems that live in and around it.”

So, while Lake Mead is at risk of further drops in water level—and is indeed forecast to hit lower levels than ever in 2025—it is unlikely to face quite the same fate as the Aral Sea.

In fact, a recent deal has been announced by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which has pledged to conserve up to 100,000 acre-feet of water in Lake Mead in 2023. Additionally, $77.6 million is being invested into water conservation projects and the protection of the Colorado River system, enough to support over 300,000 homes every year.

“There are certainly some valuable lessons that can be learned from the drying up of the Aral Sea for other parts of the world, especially those of us living in the Colorado River basin,” Andrea K. Gerlak, director of the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy and a professor in the School of Geography, Development & Environment at the University of Arizona, told Newsweek.

“The biggest lesson, perhaps, is the need to continually re-examine the uses of water in a river system to understand how those uses reflect economic and social values in the face of environmental and hydrologic realities,” she said. “It takes real political leadership and the best available science, along with an innovative and problem-solving mindset, to effectively balance these diverse uses from agriculture to cities. It isn’t a one-time decision but rather an ongoing process of dialogue that should be inclusive and participatory.”

ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

While Lake Mead may be safe from the Aral Sea’s grisly end for now, many other lakes around the world are at risk from similar water scarcity issues.

“To just focus on Africa, we can note that tensions are escalating between Ethiopia and Egypt (over the Blue and White Nile); Botswana and Namibia (over the Chobe River); Angola, Namibia and Botswana (over the Okavango River Basin); Tanzania and Malawi (over Lake Nyasa/ Lake Malawi); and Uganda and DRC (over Lake Edward),” Clack said.

“Ethiopia’s Gibe III dam on the Omo River, is set to reduce significantly the water reaching Kenya’s Lake Turkana, with over 30 percent of the lake inflow being diverted for upstream commercial irrigation projects.

“Climate change impacts both the amount and tempo of rainfall creating droughts and episodic floods. Demand can also empty reservoirs—population growth, industry and agriculture are evermore consuming of water. The second order effect then becomes disruption to food and other production. This has implications for not only economic opportunity but also cost of living and health.”

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about lakes? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Source link