-

Sentenced to life in prison as teens, two L.A. County men declared innocent on same day - December 14, 2023

-

A portion of Mulholland Drive, damaged by mudslides in winter storms, reopens - May 26, 2024

-

‘Maybe You Don’t Want to Win’ - May 26, 2024

-

Donald Trump Putting Law Enforcement in Danger: Attorney - May 25, 2024

-

Avoid the waters of these 5 L.A. County beaches this holiday weekend, public health officials say - May 25, 2024

-

Bawdy Comedy ‘Anora’ Wins Palme d’Or at Cannes Film Festival - May 25, 2024

-

Map Shows Heat Wave Zone Spread Into Five New States - May 25, 2024

-

Azusa police arrest suspected slingshot-wielding vandal - May 25, 2024

-

Donald Trump Hammers Judge Ahead of Jury Instructions - May 25, 2024

-

Sometimes U.S. and U.K. Politics Seem in Lock Step. Not This Year. - May 25, 2024

Sentenced to life in prison as teens, two L.A. County men declared innocent on same day

Although the murders they were accused of took place nearly eight years apart, teenagers Giovanni Hernandez and Miguel Solorio had the same alibi: They were at home with family.

But at each of their trials, juries looked past the testimony of loved ones who swore Hernandez and Solorio were nowhere near the scenes of the drive-by murders for which they were ultimately convicted, instead relying on witnesses who picked each teen out of a lineup.

On Wednesday, standing in courtrooms similar to those where judges once sentenced them to life without the possibility of parole, Hernandez and Solorio waited to hear two words they’d spent decades chasing: factually innocent.

“It felt like a blink of an eye, I was behind bars, sentenced to life without parole, which meant I was going to die in prison,” an emotional Solorio, 42, said at a news conference. “While it felt like it took no time at all to put me in there, it took 25 years to get me out.”

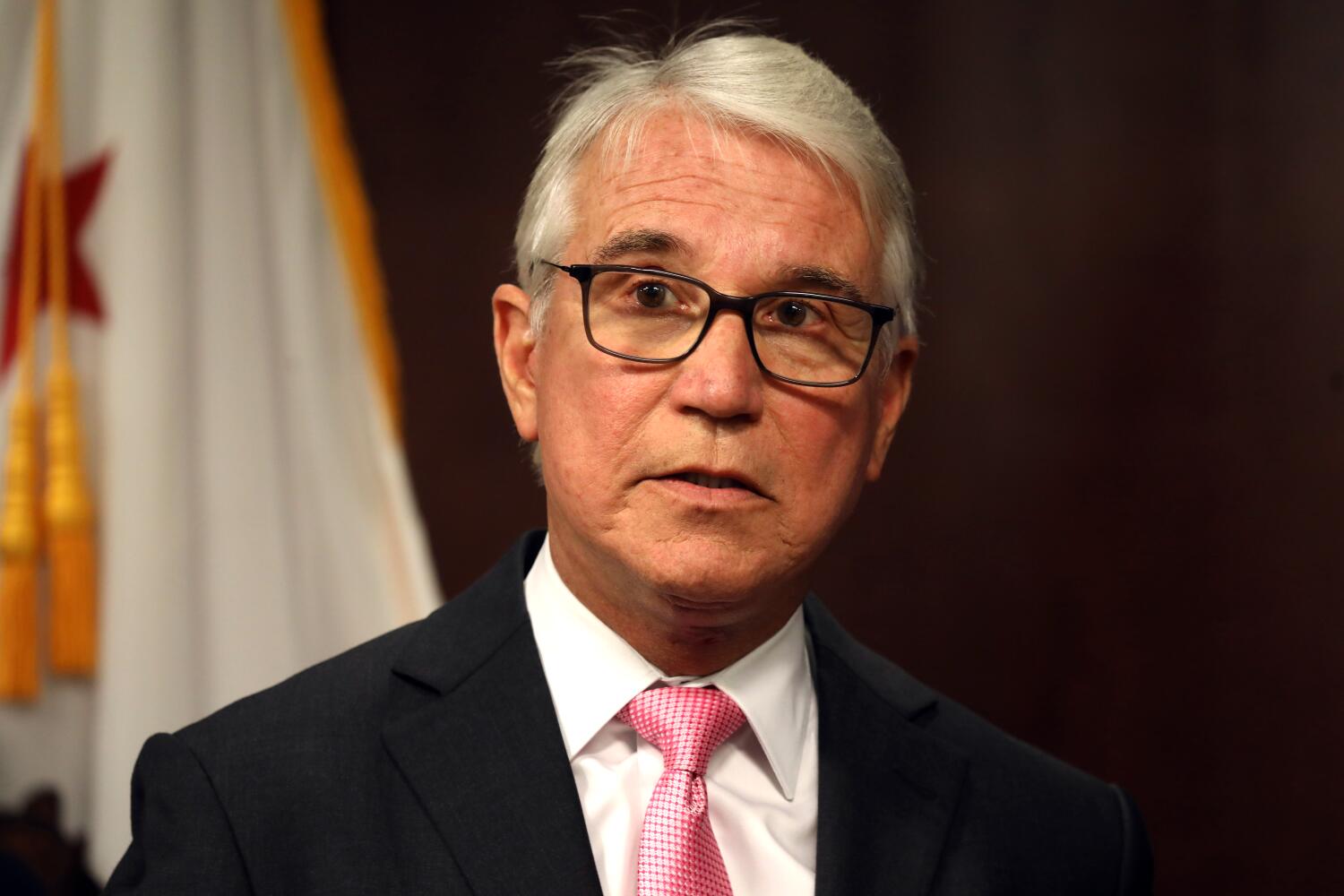

Wednesday’s rulings marked the sixth and seventh exonerations of wrongful convictions under Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, who said he has tried to shift the culture of his office’s conviction integrity unit to explore potential problems with old cases rather than defending past victories.

“I think our job is to find the truth,” he said. “I think our job is to find justice, wherever that might go.”

Hernandez was just 14 when Los Angeles police officers arrested him for the murder of teenager Gary Ortiz in 2006. Police were investigating Ortiz’s murder as retaliation in an ongoing beef between rival gangs, and placed Hernandez’s face in a photo lineup, court records show. Two witnesses picked out Hernandez, even though one told police the shooter had a “large build” and Hernandez was just 5 feet 3 and 115 pounds at the time, according to court records.

Four of Hernandez’s relatives testified he was home at the time of the shooting, and the teen’s first prosecution ended in a mistrial. But another trial in 2012 led to a conviction for murder and attempted murder, and he was hit with a de facto life sentence.

Hernandez’s case was submitted to the district attorney’s conviction integrity unit for review in 2017, not long after it was formed, but it was one of nearly 2,000 the unit initially rejected. Prosecutors took a second look at the case in 2021 at the behest of attorneys with the Juvenile Innocence and Fair Sentencing Clinic at Loyola Law School.

While prosecutors at Hernandez’s first trial had argued the location of his cellphone could not be determined, a new review showed his phone was pinging a cell tower near his home at the time of the shooting, miles from the crime scene.

After spending years in prison as a mentor and tutor to inmates — helping them with everything from Bible studies to guitar lessons — Hernandez, 31, said he plans to study education and “social transformation” at UCLA. He had been accepted to Berkeley but said he didn’t want to lose anymore time with his L.A.-based family after spending 17 years in prison.

Solorio spent nearly a quarter-century behind bars after he was wrongfully convicted of the 1998 shooting death of Mary Ann Bramlett in Whittier. Bramlett was on her way home from a bridge game when two men drove up in a car and opened fire for no apparent reason, court records show. She died four years later of a gunshot wound to the head.

Solorio had long maintained that his brother, Pedro, was actually the person involved in the killing, according to court records. On the night Bramlett was killed, Miguel Solorio and much of his family were gathered at his sister’s home. While Miguel’s car was linked to the shooting, both he and his then-girlfriend, Silvia, said Pedro left the party driving the vehicle with an unknown person. Pedro refused to testify at his brother’s trial, records show.

Over the years Silvia, who is now married to Miguel, continued to act as Solorio’s “voice,” helping him pursue post-conviction relief and struggling to help him maintain hope. Solorio described falling into a deep depression in 2014 after the California Innocence Project rejected his first petition, refusing to eat and losing nearly 60 pounds.

Years later, however, retired state public defender Ellen Eggers picked up Solorio’s case, and evidence of Pedro’s role in the shooting gained new attention from the Conviction Integrity Unit. In several letters and phone calls to his brother and Silvia, Pedro acknowledged his brother’s innocence and made comments describing another man as the shooter.

In a subsequent interview with district attorney’s office investigators, Miguel’s older brother also recounted a conversation where Pedro acknowledged another man was the shooter. That suspect is not identified in public court filings. It is not clear whether Pedro Solorio could face criminal charges.

Gascón said the Los Angeles police and sheriff’s departments have reopened both homicide investigations.

For now, Solorio is content with the fact that he just got to enjoy his first Thanksgiving with his family in 25 years. Hernandez is ready to start his college course work. But advocates for both men urged people not to lose sight of what was taken from them.

“We cannot forget how much Miguel lost. How many holidays, family gatherings, sunsets and moments he missed,” said attorney Sarah Pace, with the Northern California Innocence Project. “I don’t think any of us can truly understand how hard it would be to be arrested at 19 for a crime you didn’t commit and then be sentenced to life without parole, sentenced to die in prison.”

Source link